Die romantikus in my wil glo dat die Fenisiërs Afrika omseil het. Dus geskiedenis en ‘n soort logika om te “bewys” dat daar meer aan die wêreld is as wat ons weet, dat daar geheimenisse en verborge skatte is!

Die eerste omseiling

Die eerste omseiling van Afrika deur die Fenisiërs (ook Kanaäniete en Kartagers genoem) het in ongeveer 600 vC plaasgevind. Herodotus is in 485 gebore. Dus skryf hy oor dinge wat 115 jaar voor sy geboorte plaasgevind het. Dit is seker bykans twee geslagte later. ‘n Mens sou verwag dat die inligting nog redelik vars was en dat dit die kanse verskraal dat dit dagdrome was.

As ‘n mens fyn lees wat hy skryf, spreek hy nie twyfel uit oor die feit dat die reis plaasgevind het nie, maar slegs oor die son se posisie. Dat die implikasie van die son se posisie nie verstaan is nie, versterk die kans dat daar werklik so ‘n vaart was. Dit sou makliker gewees het om die verhaal te versin, as geweet is dat die son in die suidelike halfrond van posisie verander.

Hier is ‘n vertaling van sy opmerkings:

For my part I am astonished that men should ever have divided Libya [dit was die naam vir Afrika], Asia, and Europe as they have, for they are exceedingly unequal. Europe extends the entire length of the other two, and for breadth will not even (as I think) bear to be compared to them. As for Libya, we know it to be washed on all sides by the sea, except where it is attached to Asia. This discovery was first made by Necos [ie Necho II] , the Egyptian king, who on desisting from the canal which he had begun between the Nile and the Arabian gulf [i.e., the Red Sea], sent to sea a number of ships manned by Phoenicians, with orders to make for the Pillars of Hercules, and return to Egypt through them, and by the Mediterranean. The Phoenicians took their departure from Egypt by way of the Erythraean sea, and so sailed into the southern ocean. When autumn came, they went ashore, wherever they might happen to be, and having sown a tract of land with corn, waited until the grain was fit to cut. Having reaped it, they again set sail; and thus it came to pass that two whole years went by, and it was not till the third year that they doubled the Pillars of Hercules, and made good their voyage home. On their return, they declared - I for my part do not believe them, but perhaps others may - that in sailing round Libya they had the sun upon their right hand. In this way was the extent of Libya first discovered.

Oor die Fenisiërs se skepe en handel is daar ‘n onlangse tesis:

PHOENICIAN SHIPS: TYPES, TRENDS, TRADE ANDTREACHEROUS TRADE ROUTES deur AM SmithBladsyverwysings is hierna tensy anders aangedui.

Sy noem dat die oudste Fenisiëse voorbeeld van ‘n skip uit 1400 vC dateer (p23), dat die Fenisiërs vermaarde handelaars was met kolonies en lang gevaarlike seehandelsroetes trotseer het (p6, p160 et seq). Hulle het met

duur goedere (bv goud) handel gedryf en was welvarend.

Die Fenisiëse skeepsredery is egter veel ouer as 1400 jaar vC.

In her brilliant book “The Phoenicians and the West” (1993), Maria Eugenia Aubet

provides a wealth of information about the Phoenicians, both in their heartland along

the Levantine coast, as well as in their western colonies. As we saw in the quote from

her book in the previous chapter (see 1.9.5), she is of the opinion that the Phoenicians

learned how to build ships from the Egyptians (Aubet 1993:146). For clarity sake the

quote gets repeated here once more:

The first explicit mention of Phoenician ships refers to a fleet of forty

merchant ships carrying cedar, which left a Phoenician port bound for Egypt

around the year 3000 BC. From at least the middle of the third millennium

we have evidence of large merchant ships – the ‘ships of Byblos’ – on the

open sea trading with Egypt. It is partly to this long experience that the

reputation of the Phoenician pilots as experts in the arts of navigation is due,

also that of the naval engineers of Tyre, highly valued as shipbuilders and

sought after by other eastern monarchies like Israel. Byblos, Tyre and Sidon

had learnt all these techniques from Egypt, a country with a long shipping

tradition that had grown out of travel on the Nile, principally by sail but using

oars for auxiliary propulsion (Aubet 1993:146).Bron: Smith se tesis, p20. Sy toon aan dat die Fenisiërs hul skepe gebou het uit die samestelling van ‘n hele paar verskillende volke se beste idees.

As voorbeeld van die Fenisiërs se handelsware kan ‘n mens die gesogte purper klede noem, raar honde, hout (seder) en perde (p6). Ook veral tin, koper, goud. Verskillende soorte skepe is gebruik en die grootstes kon 450 ton vrag dra (p 58). Die ontwerp van die skepe is vanaf verskillende bronne verkry, om sterk skepe te bou wat ook die oop see kon trotseer (p 57).

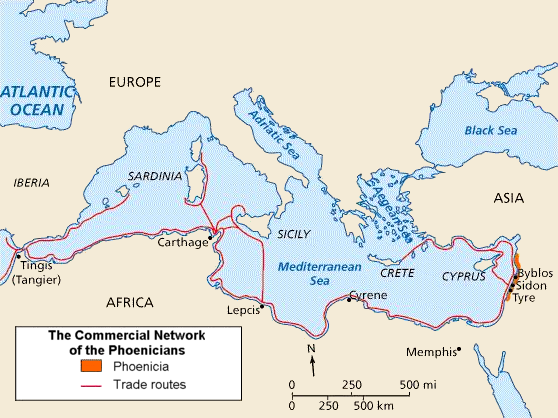

Die reik van hul gewone handelsroetes kan op die kaart gesien word:

Uit Herodotus se relaas kan dit wees dat die

primêre motief vir die reis verdediging teen die Babiloniërs was:

The circumnavigation of Africa must somehow have been related to Necho's defense projects. He asked for Phoenician assistance because the Phoenicians (who lived in modern Lebanon) were excellent sailors and had several colonies in the West, such as Carthage and the islet of Mogador opposite modern Essaouira. The Phoenicians must have been happy to help the Egyptians, because they shared the Babylonian enemy.

Daar is heelwat hedendaagse

omstredenheid oor of die reis wel plaasgevind het.

Reise wat die omvaart voorafgegaan het

Vroeëre ontdekkingsreise sou die aanpak van so ‘n skema as ‘n moontlikheid geskep het.

Van die vroegste ontdekkers was koningin Hatsjepsoet se seelui.

Hatsjepsoet

In die jaar 1493-1492 vC het roeiskepe van die Egiptiese koningin Hatsjepsoet van Egipte na die land van Punt (wat ook Somalië ingesluit het, gevaar om na die wondere van Afrika te soek. Hulle het Kaap Guardafui bereik.

APJ van Rensburg: Aspekte van die geskiedenis van Afrika, Haum, 1974, p37

Salomo

Volgens die Bybel het hy met hulp van seevaarders van Hiram van Tarsus teen 945 vC ape, poue, ivoor, goud en silwer in die land Ofir gaan haal. Party sê dis Sofala (Zimbabwe), maar miskien is Somalië meer korrek.

Van Rensburg op cit p38.

Hanno

Hanno se reis se moontlike datum plaas dit baie naby aan die omvaart. Indien voor die omvaart, het dit die aanpak daarvan geïnspireer – anders was dit dalk ‘n gevolg daarvan.

Carthage dispatched [5th or 6th Century bC] Hanno at the head of a fleet of 60 ships to explore and colonize the northwestern coast of Africa.[3] He sailed through the straits of Gibraltar, founded or repopulated seven colonies along the African coast of what is now Morocco, and explored significantly farther along the Atlantic coast of the continent. Hanno encountered various indigenous peoples on his journey and met with a variety of welcomes.

…

The only source of his voyage is a Greek periplus. According to some modern analyses of his route, Hanno's expedition could have reached as far south as Gabon, however, others have taken him no further than southern Morocco.

BronA periplus (/ˈpɛrɪplʌs/) is a manuscript document that lists the ports and coastal landmarks, in order and with approximate intervening distances, that the captain of a vessel could expect to find along a shore.[1] In that sense the periplus was a type of log. It served the same purpose as the later Roman itinerarium of road stops; however, the Greek navigators added various notes, which if they were professional geographers (as many were) became part of their own additions to Greek geography.

The form of the periplus is at least as old as the earliest Greek historian, the Ionian Hecataeus of Miletus. The works of Herodotus and Thucydides contain passages that appear to have been based on peripli.[2]

BronPeriplus account

The "Mount Cameroon" personnel interpretation of the route.

The primary source for Hanno's expedition is a Greek periplus, supposedly a translation of a tablet Hanno is reported to have hung up on his return to Carthage in the temple of Ba'al Hammon, whom Greek writers identified with Kronos. The full title translated from Greek is The Voyage of Hanno, commander of the Carthaginians, round the parts of Libya beyond the Pillars of Heracles, which he deposited in the Temple of Kronos.[citation needed]

In the fifth century, the text was translated into a rather mediocre Greek. It was not a complete rendering; several abridgments were made. The abridged translation was copied several times by Greek and Byzantine clerks. Currently, there are only two copies, dating back to the ninth and the fourteenth centuries.[4]

The first of these manuscripts is known as the Palatinus Graecus 398 and can be studied in the University Library of Heidelberg.[9] The other text is in the Codex Vatopedinus 655, found in the Vatopedi monastery in Mount Athos, Greece, and dated to the beginning of the 14th century; the codex is divided between the British Library[10] and the French Bibliothèque Nationale.[4][11]

BronModern analysis of the route

A number of modern scholars have commented upon Hanno's voyage. In many cases, the analysis has been to refine information and interpretation of the original account. William Smith points out that the complement of personnel totalled 30,000, and that the core mission included the intent to found Carthaginian (or in the older parlance 'Libyophoenician') towns. [15] Some scholars have questioned whether this many people accompanied Hanno on his expedition, and suggest 5,000 is a more accurate number.[4] Robin Law notes that "It is a measure of the obscurity of the problem that while some commentators have argued that Hanno reached the Gabon area, others have taken him no further than southern Morocco."[16]

Harden reports a general consensus that the expedition reached at least as far as Senegal.[17] Some agree he could have reached Gambia. However, Harden mentions disagreement as to the farthest limit of Hanno's explorations: Sierra Leone, Cameroon, or Gabon. He notes the description of Mount Cameroon, a 4,040-metre (13,250 ft) volcano, more closely matches Hanno's description than Guinea's 890-metre (2,920 ft) Mount Kakulima. Warmington prefers Mount Kakulima, considering Mount Cameroon too distant.[18]

Warmington suggests[19] that difficulties in reconciling the account's specific details with present geographical understanding are consistent with classical reports of Carthaginian determination to maintain sole control of trade into the Atlantic.

This report was the object of criticism by some ancient writers, including the Pliny the Elder, and in modern times a whole literature of scholarship has grown up around it. The account is incoherent and at times certainly incorrect, and attempts to identify the various places mentioned on the basis of the sailing directions and distances almost all fail. Some scholars resort to textual emendations, justified in some cases; but it is probable that what we have before us is a report deliberately edited so that the places could not be identified by the competitors of Carthage. From everything we know about Carthaginian practice, the resolute determination to keep all knowledge of and access to the western markets from the Greeks, it is incredible that they would have allowed the publication of an accurate description of the voyage for all to read. What we have is an official version of the real report made by Hanno which conceals or falsifies vital information while at the same time gratifying the pride of the Carthaginians in their achievements. The very purpose of the voyage, the consolidation of the route to the gold market, is not even mentioned.

The historian Raymond Mauny, in his 1955 article La navigation sur les côtes du Sahara pendant l'antiquité, argued that the ancient navigators (Hannon, Euthymène, Scylax, etc ..) could not have sailed south in the Atlantic farther than Cape Bojador. He pointed out that antique geographers knew of the Canary Islands but nothing further south. Ships with square sails, without stern rudder, might navigate south, but the winds and currents throughout the year would prevent the return trip from Senegal to Morocco. Oared ships might be able to achieve the return northward, but only with very great difficulties. Mauny assumed that Hanno did not get farther than the Drâa. He attributed artifacts found on Mogador island to the expedition described in the Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax and notes that no evidence of Mediterranean trade further south had yet been found. The author ends by suggesting archaeological investigation of the islands along the coast, such as Cape Verde, or the île de Herné (Dragon Island near Dakhla, Western Sahara) where ancient adventurers may have been stranded and settled.[20]

Reise wat gevolg het op die omvaart

Sataspes

Herodotus

beskryf ook ‘n tweede reis:

Next to these Phoenicians the Carthaginians, according to their own accounts, made the voyage. For Sataspes, son of Teaspes the Achaemenian, did not circumnavigate Libya, though he was sent to do so; but, fearing the length and desolateness of the journey, he turned back and left unaccomplished the task which had been set him by his mother. This man had used violence towards a maiden, the daughter of Zopyrus, son of Megabyzus, and King Xerxes was about to impale him for the offence, when his mother, who was a sister of Darius, begged him off, undertaking to punish his crime more heavily than the king himself had designed. She would force him, she said, to sail round Libya and return to Egypt by the Arabian gulf. Xerxes gave his consent; and Sataspes went down to Egypt, and there got a ship and crew, with which he set sail for the Pillars of Hercules. Having passed the Straits, he doubled the Libyan headland, known as Cape Soloeis, and proceeded southward.

Following this course for many months over a vast stretch of sea, and finding that more water than he had crossed still lay ever before him, he put about, and came back to Egypt. Thence proceeding to the court, he made report to Xerxes, that at the farthest point to which he had reached, the coast was occupied by a dwarfish race, who wore a dress made from the palm tree. These people, whenever he landed, left their towns and fled away to the mountains; his men, however, did them no wrong, only entering into their cities and taking some of their cattle. The reason why he had not sailed quite round Libya was, he said, because the ship stopped, and would no go any further. Xerxes, however, did not accept this account for true; and so Sataspes, as he had failed to accomplish the task set him, was impaled by the king's orders in accordance with the former sentence.

Die Kartagers waarna verwys word was oorspronklik ook Fenisiërs. Dus geld die gesketsde agtergrond van handel, skepe en bekwaamheid ook vir hulle. ‘n Mens kan aflei dat Sataspes miskien Wes-Afrika se trope gehaal het.

Hy was ‘n Griek wat via die see ongeveer 530 vC die Senegalrivier bereik het .

Polybius

When Scipio defeated the Carthaginians in the Third Punic War, Polybius remained his counsellor. The Achaean hostages were released in 150 BC, and Polybius was granted leave to return home, but the next year he went on campaign with Scipio Aemilianus to Africa, and was present at the Sack of Carthage in 146, which he later described. Following the destruction of Carthage, Polybius likely journeyed along the Atlantic coast of Africa, as well as Spain. BronDie rede vir sy reis was onder andere moontlik om die verslane Kartagers se Wes-Afrika-ryk te bespied – veral omdat hulle baie geheimsinnig daaroor was. Hy het miskien sover as die Senegalrvier gevorder.

Eichel, M., & Todd, J. (1976). A Note on Polybius' Voyage to Africa in 146 B.C. Classical Philology, 71(3), 237-243. Retrieved from

www.jstor.org/stable/267960, p238.

Met 'n Fenisiëse skip om Afrika in die 21 ste Eeu. (Sien Trog se skakels in die vorige pos)

Also the successful circumnavigation by the Phoenicians of the entire continent of

Africa, as ordered by Pharaoh Necho of Egypt (610-595 BCE), should not be written

off as impossible (Markoe 2000:188). To our modern mind it may seem impossible for

small vessels like those of the Phoenicians to circumnavigate the Cape of Storms and

brave the mighty Atlantic Ocean. Not even two years ago however, a fleet of small

sailing yachts set sail out of Simonstown early in December to sail to St. Helena. Our

friend, retired Vice–Admiral of the South African Navy Martin Trainor, took part in this

regatta, called “The Governor’s Cup”. The voyage was recorded and subsequently

broadcast on SABC in two parts. The yacht he crewed on as navigator reached St.

Helena without a problem, as did most of the yachts that had departed with them.

These yachts were not bigger than about 10 - 15 meters maximum.Smith Thesis op cit p174

As the writing of this dissertation drew to an end, new information came to light

regarding the recent circumnavigation of Africa with the replica of a Phoenician ship.

This ship set sail from the Syrian coast in 2009 and circumnavigated the continent of

Africa over a period of 3 years, with Phillip Beale as the captain and with volunteer

crews (See Figure 10-8). The ship even spent time in Cape Town in 2010.

Why there was nothing mentioned in our local newspapers about this at the time is the

question that comes to mind, but maybe there was too much attention for the World

Cup Soccer. This year (2012) the ship sailed from Lebanon to London, where it was on

display for a number of weeks 27 . This entire enterprise shows once again, that it is

possible to sail the high seas, and circumnavigate Africa with ships of the size the

Phoenicians used.Smith Thesis op cit pp174-175

Fenisiëse inskrywing op rots in Brasilië

I

n closing the Parahyba inscription can be mentioned (See Figure 10-9). This

inscription on a rock face, found in Parahyba in Brazil, has been the subject of much

debate as to whether it is genuine or a fake. The inscription recounts the arrival of a

Phoenician ship, which had been thrown off course by a storm off the coast of Africa,

and had landed up on an unknown shore. The entire text in translation, as quoted by

Sullivan reads as follows:

We are sons of Canaan from Sidon, the City of the King. Commerce has

cast us on this distant shore, a land of mountains. We set (sacrificed) a

youth for the exalted Gods and Goddesses in the nineteenth year of Hiram,

our mighty king. We embarked from Ezion-Geber into the Red Sea and

voyaged with ten ships. We were at sea together for two years around the

land belonging to Ham (Africa) but were separated by a storm (literally: from

the hand of Baal) and we were no longer with our companions. So we have

come here, twelve men and three women, on a G shore, which I, the

Admiral, control. But auspiciously may the Gods and Goddesses favour us.”

(Sullivan 2001:xix).

Despite the fact that the inscription has been declared a fake on the basis of linguistic

aspects, there are some points that do not seem to have been taken into account in

the analysis of its veracity.

Figure 10-9: Facsimile copy of Parahyba inscription (Spanuth 1985:81).

In the first place the question is: “Who would still have been able to write such a text

many centuries afterwards, with the limited knowledge of the Phoenician language at

that time?” Secondly: “Why would anyone have wanted to go through the trouble of

composing such a text, and inscribing it on a rock face in a place like Parahyba?”

Thirdly: “Who would have thought of adding the aspect of sacrificing a youth after the

safe landing on the shore?” And fourthly: “Why are other aspects not taken into

account in the judgement of whether it is fake or real, such as the fact that especially

the Cape of Good Hope (also nicknamed the Cape of Storms, and in Portuguese:

Cabo Tormentoso) here in South Africa, as well as the Skeleton Coast of Namibia are

known for their severe storms? A ship that gets thrown off course can easily end up in

the current that runs across the South Atlantic in westerly direction, which lands up at

the coast of Brazil, exactly at Parahyba (Ormeling [ed.] 1971:152,135) (See Figure

10-10). A further aspect is something that Vice-Admiral Trainor mentioned in the

televised program about the regatta from Simonstown to St. Helena, and that is that

there is an underwater mountain range off the coast of Namibia called the Walvis

ridge, which can cause enormous waves, that can throw a ship off course. This too

could have been an additional factor in a ship ending up in the westerly gulfstream that

runs to the Brazilian coast. Maybe the Parahyba inscription is not a fake after all.

Figure 10-10: Ocean currents between Africa and South America. Parahyba indicated

with red arrow (Ormeling 1971:152,135).

Smith Thesis op cit pp175-177

Fenisiëse geheimhouding van handelsinliging

“Whatever acquaintance with the remote regions of the earth the Phoenicians or Carthaginians may have acquired, was concealed from the rest of mankind with a mercantile jealousy. Everything relative to the course of their navigation was not only a mystery of trade, but a secret of state… As neither the progress of the Phoenician or Carthaginian discoveries, nor the extent of their navigation, were communicated to the rest of mankind, all memorials of their extraordinary skill in naval affairs seem in a great measure to have perished when the maritime power of the former was annihilated, &c…” (“Notes To Chapter V”, Num. 72. A New History of the Conquest of Mexico, by Robert Anderson Wilson. Philadelphia: James Challen & Son, 1859)

Eichel, M., & Todd, J. (1976). A Note on Polybius' Voyage to Africa in 146 B.C. Classical Philology, 71(3), 237-243. Retrieved from

www.jstor.org/stable/267960, p237n2, p238.

Honde en Katte

Gegewe dat die Fenisiërs handel gedryf het met honde, is die volgende miskien meer betekenisvol as wat ‘n mens mag dink.

The royal dog of Madagascar is the breed called the Bichon and their spread is put to Phoenicians and other sailors. A somewhat smaller island is Lamu (off Kenya). Here are cats with many traits shared with those depicted in various Egyptian media.. Neil Todd (Scientific American 1977), James Baldwin (Carnivores Genetics Newsletter 1979) and H. & M. Bourne (Feline Hist. Group Newsletter 2002) show their spread. J.O. Lucas (see below) shows many west African words for cats owing nothing to Europe but may owe something to Egypt. Cats were so highly regarded that well into the 19th c., Yemeni crews in east Africa refused to sail unless a cat was on board. The crews that are held to have aided spread the ships’-cat are again Phoenician plus others.The Phoenician in East Africa‘n Relaas van ander handelsware en simbole wat dui op Fenisiëse teenwoordigheid ver langs die ooskus van Afrika kan in

The Phoenicians in East Africa gevind word.Dit sluit in afbeeldings van voëls, die drie-tandvurk van Poseidon, seereise wat in vlakwater eindig (Sofala/Mosambiek), eilande waar skepe vergaan het, juwele wat verhandel is met inboorlinge van Afrika

Kaarte

Kaarte na 600 vC dui op ‘n see wat Afrika aan die suidpunt omring (sien bv JO Thompson: Classical Atlas, Dent & Sons, 1966 p1-5) . Was dit miskien onder invloed van die omvaart?

Samevatting

Die Fenisiërs was kranige skeepslui en skeepbouers met baie eeue se ondervinding op daardie gebiede. Skeepsvaart en handel was die essensie van hul hele bestaan. Afrika se kuslyne was gedeeltelik bekend onder andere as gevolg van ander ontdekkingsreise en handel al met die kus langs. Hulle het moeite gedoen om hul kennis weg te steek wat miskien verklaar waarom so min omtrent die reis bekend is.

Veral die feit dat die posisie van die son verskil tussen die suidelike en noordelike halfrond en dat dit genoem word, is ‘n sterk aanduiding dat Afrika wel deur hulle omseil is. Die aantal verkenningsvaarte langs die Afrika-kus na 600 vC dui moontlik daarop dat die omvaart ander ekspedisies aangewakker het. Miskien kan iets daarin gelees word dat kaarte wat die suidpunt van Afrika aandui as omring met see, vanaf sowat 500 vC dateer – dalk geïnspireer deur die omvaart. Die dryfveer vir die betrokke omvaart kan hoofsaaklik as militêre verkenning gesien word.

Dat so ‘n vaart moontlik was, word gestaaf deur ‘n 21ste eeu se omvaart in ‘n replika van destyds se skepe.

Handels-items van so ver as Mosambiek, dui moontlik op vaarte wat tot baie naby aan die suidpunt van Afrika gekom het. Die ooskus van Afrika is gedeeltelik bevaar deur Afrikane selfs voor die omvaart.

Algemeenen.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phoeniciaen.wikipedia.org/wiki/CanaanOnlangse DNA-toetse dui op ‘n antieke Noord – Europese invloed